"That will be Ukraine," says Rupert Pearce, pointing to a pinkish cell on an enormous electronic screen in Inmarsat's London headquarters. The colour indicates heavy demand on the group's satellite communications network. The world's media, big users of Inmarsat's $700 (£421) satellite phones and 11 satellites in orbit 22,000 miles above the earth, are lighting up Ukraine, he suspects.

The cells are darker off the south-west coast of Australia. It's there, though, that Inmarsat finds itself at the centre of another global story. It is the previously low-profile UK company that helped to establish that Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 almost certainly crashed in the southern Indian Ocean. Satellite data collected in this control room – when sliced, analysed and modelled – provided the key clues in narrowing the search.

The Malaysian government has acknowledged the importance of the analysis by Inmarsat and the UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch. However, Pearce, 50, and chief executive since 2012, is oddly reluctant to claim Inmarsat's contribution was critical. "I don't know whether you can say that honestly," he says, pointing out that he can't know what other sources of information were used by official investigators.

"Our job was to get our heads down, look at our data, to try to turn that into meaningful intelligence that could support the investigation. Full stop. What that turned into, where it went, whether it was actionable, that was for the accident investigation group. My belief is that there were many types of information coming in which they used to form a three-dimensional picture."

What is clear, though, is that Inmarsat was the first to advance and support the theory that MH370 must have flown on a northerly or southerly arc after the final communication from the cockpit. This conclusion was based on analysis of the "pings" from an Inmarsat satellite above the Indian Ocean to the aircraft's antenna. Inmarsat's communication technology is installed on most of the world's intercontinental aircraft and the system works like a mobile phone network, constantly checking for connectivity via a so-called "handshake."

"Dozens" of Inmarsat engineers – mostly at the HQ on Old Street's Silicon Roundabout – arrowed down the likely flight path, basing their calculations on the shift in frequencies created by a moving object (the plane) connecting with a fixed object (the satellite).

That, at least, is the shorthand version. Pearce won't be drawn on the finer details of an exercise that has impressed aviation experts: "You dig down a fraction beneath the apparently facile surface and it's incredibly complex and skilful engineering and extremely complex to understand requiring a lot of thought and discussion," he says. "It isn't straightforward. We haven't done anything like this before."

The reluctance to discuss details, he says, is to minimise misleading noise: "The blogosphere is full of rumours, innuendo, supposition that will take the slightest bit of information and turn it into conjecture. I can only imagine how wounding and damaging and chaotic that is to those people who have potentially lost loved ones. So we are trying to restrict our information to channelling it through the investigation."

Before this month, Inmarsat was known in the City as the satellite company with a volatile share price and a habit of upsetting some of its shareholders with rows over the pay of its executive chairman, Andrew Sukawaty. Now it is famous. There is no commercial benefit for Inmarsat in assisting the MH370 investigation, Pearce stresses. Nevertheless, in normal clinical style, the City's attention has turned to Inmarsat as an investment. The share price has risen 9% in the past fortnight.

The company was born in 1979 as the International Maritime Satellite Organisation, a not-for-profit venture created by the International Maritime Organisation to enable ships to stay in contact with shore and call for help; emergency distress calls are still routed as priority for free.

It was privatised in 1999, bought by private equity houses Apax and Permira in 2003, then floated in London two years later, trebling in value in the next half-decade. It was briefly a member of the FTSE 100 index before a fall in the share price in 2010 and 2011. Revenues from the core maritime business (about 60% of last year's group total of $1.25bn) stalled in the global downturn. Then came the collapse into bankruptcy protection of LightSquared, a US telecoms firm planning to build a wireless broadband network in the US using spectrum leased from Inmarsat's satellites. The US military's withdrawal from Afghanistan has been another headwind.

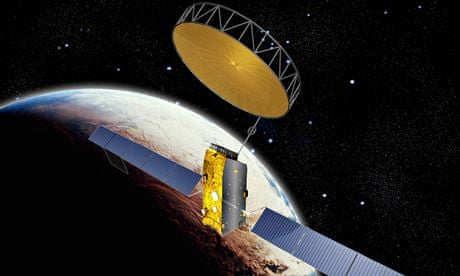

Now the share price has almost regained its old levels as attention has turned to the potential of Inmarsat's latest generation of satellites, called Global Xpress. The first, built by Boeing, was launched last December from Kazakhstan and two more will go up later this year. A fourth is on order as a reserve in case of a blow-up on the launchpad, not unknown in this industry, although Inmarsat has never lost a satellite. Pearce calls 2014 "a year of transition leading to transformational growth".

The kit is substantial. Each Global Xpress satellite costs about $400m and is the size of a London bus. The new generation can run 100 times faster than the old technology and the potential size of new markets is said to be worth $3bn a year across maritime, aviation, energy, government and commercial fields.

In aviation, where Inmarsat's broadband service is already on 5,000 planes, it could mean high-quality 3D pictures being received by passengers on planes. Business people flying across China could be able to join video conferences hosted in the US. "That's the era that's coming," says Pearce.

The new technology will also be capable of streaming critical positioning and cockpit data from aircraft in real time, reducing the urgency of finding the black box in cases like MH370. Should such an improvement be made mandatory? Pearce is back on his conservative script: "That's another issue that will have to be looked at. We can support those services. But it is far, far too early to make calm, mature decisions like that."